Source code

Revision control

Copy as Markdown

Other Tools

# Power profiling

This article covers important background information about power

profiling, with an emphasis on Intel processors used in desktop and

laptop machines. It serves as a starting point for anybody doing power

profiling for the first time.

## Basic physics concepts

is the rate of doing

It is equivalent to an amount of

consumed per unit time. In SI units, energy is measured in Joules, and

power is measured in Watts, which is equivalent to Joules per second.

Although power is an instantaneous concept, in practice measurements of

it are determined in a non-instantaneous fashion, i.e. by dividing an

energy amount by a non-infinitesimal time period. Strictly speaking,

such a computation gives the *average power* but this is often referred

to as just the *power* when context makes it clear.

In the context of computing, a fully-charged mobile device battery (as

found in a laptop or smartphone) holds a certain amount of energy, and

the speed at which that stored energy is depleted depends on the power

consumption of the mobile device. That in turn depends on the software

running on the device. Web browsers are popular applications and can be

power-intensive, and therefore can significantly affect battery life. As

a result, it is worth optimizing (i.e. reducing) the power consumption

caused by Firefox and Firefox OS.

## Intel processor basics

### Processor layout

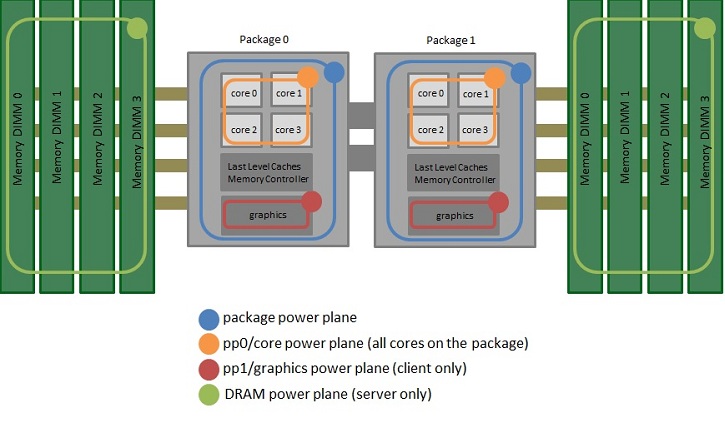

The following diagram (from the [Intel Power Governor

shows how machines using recent Intel processors are constructed.

The important points are as follows.

- The processor has one or more *packages*. These are part of the

actual processor that you buy from Intel. Client processors (e.g.

Core i3/i5/i7) have one package. Server processors (e.g. Xeon)

typically have two or more packages.

- Each package contains multiple *cores*.

- Each core typically has

which means it contains two logical *CPUs*.

- The part of the package outside the cores is called the [*uncore* or

various components including the L3 cache, memory controller, and,

for processors that have one, the integrated GPU.

- RAM is separate from the processor.

### C-states

Intel processors have aggressive power-saving features. The first is the

ability to switch frequently (thousands of times per second) between

active and idle states, and there are actually several different kinds

of idle states. These different states are called

*[C-states](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Configuration_and_Power_Interface#Processor_states).*

C0 is the active/busy state, where instructions are being executed. The

other states have higher numbers and reflect increasing deeper idle

states. The deeper an idle state is, the less power it uses, but the

longer it takes to wake up from.

Note: the [ACPI

specifies four states, C0, C1, C2 and C3. Intel maps these to

processor-specific states such as C0, C1, C2, C6 and C7. and many tools

report C-states using the latter names. The exact relationship is

confusing, and chapter 13 of the [Intel optimization

has more details. The important thing is that C0 is always the active

state, and for the idle states a higher number always means less power

consumption.

The other thing to note about C-states is that they apply both to cores

and the entire package --- i.e. if all cores are idle then the entire

package can also become idle, which reduces power consumption even

further.

The fraction of time that a package or core spends in an idle C-state is

called the *C-state residency*. This is a misleading term --- the active

state, C0, is also a C-state --- but one that is nonetheless common.

Intel processors have model-specific registers (MSRs) containing

measurements of how much time is spent in different C-states, and tools

such as [powermetrics](powermetrics.md)

(Mac), powertop and

[turbostat](turbostat.md) (Linux) can

expose this information.

A *wakeup* occurs when a core or package transitions from an idle state

to the active state. This happens when the OS schedules a process to run

due to some kind of event. Common causes of wakeups include scheduled

timers going off and blocked I/O system calls receiving data.

Maintaining C-state residency is crucial to keep power consumption low,

and so reducing wakeup frequency is one of the best ways to reduce power

consumption.

One consequence of the existence of C-states is that observations made

during power profiling --- even more than with other kinds of profiling

--- can disturb what is being observed. For example, the Gecko Profiler

takes samples at 1000Hz using a timer. Each of these samples can trigger

a wakeup, which consumes power and obscures Firefox's natural wakeup

patterns. For this reason, integrating power measurements into the Gecko

Profiler is unlikely to be useful, and other power profiling tools

typically use much lower sampling rates (e.g. 1Hz.)

### P-states

Intel processors also support multiple *P-states*. P0 is the state where

the processor is operating at maximum frequency and voltage, and

higher-numbered P-states operate at a lower frequency and voltage to

reduce power consumption. Processors can have dozens of P-states, but

the transitions are controlled by the hardware and OS and so P-states

are of less interest to application developers than C-states.

## Power and power-related measurements

There are several kinds of power and power-related measurements. Some

are global (whole-system) and some are per-process. The following

sections list them from best to worst.

### Power measurements

The best measurements are measured in joules and/or watts, and are taken

by measuring the actual hardware in some fashion. These are global

(whole-system) measurements that are affected by running programs but

also by other things such as (for laptops) how bright the monitor

backlight is.

- Devices such as ammeters give the best results, but these can be

expensive and difficult to set up.

- A cruder technique that works with mobile machines and devices is to

run a program for a long time and simply time how long it takes for

the battery to drain. The long measurement times required are a

disadvantage, though.

### Power estimates

The next best measurements come from recent (Sandy Bridge and later)

Intel processors that implement the *RAPL* (Running Average Power Limit)

interface that provides MSRs containing energy consumption estimates for

up to four *power planes* or *domains* of a machine, as seen in the

diagram above.

- PKG: The entire package.

- PP0: The cores.

- PP1: An uncore device, usually the GPU (not available on all

processor models.)

- DRAM: main memory (not available on all processor models.)

The following relationship holds: PP0 + PP1 \<= PKG. DRAM is independent

of the other three domains.

These values are computed using a power model that uses

processor-internal counts as inputs, and they have been

as being fairly accurate. They are also updated frequently, at

approximately 1,000 Hz, though the variability in their update latency

means that they are probably only accurate at lower frequencies, e.g. up

to 20 Hz or so. See section 14.9 of Volume 3 of the [Intel Software

Developer's

Manual](http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/processors/architectures-software-developer-manuals.html)

for more details about RAPL.

Tools that can take RAPL readings include the following.

- `tools/power/rapl`: all planes; Linux and Mac.

- [Intel Power

Gadget](intel_power_gadget.md): PKG and

PP0 planes; Windows, Mac and Linux.

- [powermetrics](powermetrics.md): PKG

plane; Mac.

- [perf](perf.md): all planes; Linux.

- [turbostat](turbostat.md): PKG, PP0 and

PP1 planes; Linux.

Of these,

[tools/power/rapl](tools_power_rapl.md) is

generally the easiest and best to use because it reads all power planes,

it's a command line utility, and it doesn't measure anything else.

### Proxy measurements

The next best measurements are proxy measurements, i.e. measurements of

things that affect power consumption such as CPU activity, GPU activity,

wakeup frequency, C-state residency, disk activity, and network

activity. Some of these are measured on a global basis, and some can be

measured on a per-process basis. Some can also be measured via

instrumentation within Firefox itself.

The correlation between each proxy measure and power consumption is hard

to know and can vary greatly. When used carefully, however, they can

still be useful. This is because they can often be measured in a more

fine-grained fashion than power measurements and estimates, which is

vital for gaining insight into how a program can reduce power

consumption.

Most profiling tools provide at least some proxy measurements.

### Hybrid proxy measurements

These are combinations of proxy measurements. The combinations are

semi-arbitrary, they amplify the unreliability of proxy measurements,

and unlike non-hybrid proxy measurements, they don't have a clear

physical meaning. Avoid them.

The most notable example of a hybrid proxy measurement is the ["Energy

Impact" used by OS X's Activity

[Monitor](activity_monitor_and_top.md#What-does-Energy-Impact-measure).

## Ways to user power-related measurements

### Low-context measurements

Most power-related measurements are global or per-process. Such

low-context measurements are typically good for understand *if* power

consumption is good or bad, but in the latter case they often don't

provide much insight into why the problem is occurring, which part of

the code is at fault, or how it can be fixed. Nonetheless, they can

still help improve understanding of a problem by using *differential

profiling*.

- Compare browsers to see if Firefox is doing better or worse than

another browser on a particular workload.

- Compare different versions of Firefox to see if Firefox has improved

or worsened over time on a particular workload. This can identify

specific changes that caused regressions, for example.

- Compare different configurations of Firefox to see if a particular

feature is affecting things.

- Compare different workloads. This can be particularly useful if the

workloads only vary slightly. For example, it can be useful to

gradually remove elements from a web page and see how the

power-related measurements change. Even just switching a tab from

the foreground to the background can make a difference.

### High-context measurements

A few power-related measurements can be obtained in a high-context

fashion, e.g. with stack traces that clearly pinpoint specific parts of

the code as being responsible.

- Standard performance profiling tools that measure CPU usage or

proxies of CPU usage (such as instruction counts) typically provide

high-context measurements. This is useful because high CPU usage

typically causes high power consumption.

- Some tools can provide high-context wakeup measurements:

[dtrace](dtrace.md) (on Mac) and

[perf](perf.md) (on Linux.)

- Source-level instrumentation, such as [TimerFirings

logging](timerfirings_logging.md), can

identify which timers are firing frequently.

## Power profiling how-to

This section aims to put together all the above information and provide

a set of strategies for finding, diagnosing and fixing cases of high

power consumption.

- First of all, all measurements are best done on a quiet machine that

is running little other than the program of interest. Global

measurements in particular can be completely skewed and unreliable

if this is not the case.

- Find or confirm a test case where Firefox's power consumption is

high. "High" can most easily be gauged by comparing against other

browsers. Use power measurements or estimates (e.g. via

[tools/power/rapl](tools_power_rapl.md),

or `mach power` on Mac, or [Intel Power

Gadget](intel_power_gadget.md) on

Windows) for the comparisons. Avoid lower-quality measurements,

especially Activity Monitor's "Energy Impact".

- Try using differential profiling to narrow down the cause.

- Try turning hardware acceleration on or off; e10s on or off;

Flash on or off.

- Try putting the relevant tab in the foreground vs. in the

background.

- If the problem manifests on a particular website, try saving a

local copy of the site and then manually removing HTML elements

to see if a particular page feature is causing the problem

- Many power problems are caused by either high CPU usage or high

wakeup frequency. Use one of the low-context tools to determine if

this is the case (e.g. on Mac use

[powermetrics](powermetrics.md).) If

so, follow that up by using a tool that gives high-context

measurements, which hopefully will identify the cause of the

problem.

- For high CPU usage, many profilers can be used: Firefox's dev

tools profiler, the Gecko Profiler, or generic performance

profilers.

- For high wakeup counts, use

[dtrace](dtrace.md) or

[perf](perf.md) or [TimerFirings logging](timerfirings_logging.md).

- On Mac workloads that use graphics, Activity Monitor's "Energy"

tab can tell you if the high-performance GPU is being used, which

uses more power than the integrated GPU.

- If neither CPU usage nor wakeup frequency identifies the problem,

more ingenuity may be needed. Looking at other measurements (C-state

residency, GPU usage, etc.) may be helpful.

- Animations are sometimes the cause of high power consumption. The

[animation

inspector](/devtools-user/page_inspector/how_to/work_with_animations/index.rst#animation-inspector)

in the Firefox Devtools can identify them. Alternatively, [here is

an

of how one developer diagnosed two animation-related problems the

hard way (which required genuine platform expertise).

- The approximate cause of power problems often isn't that hard to

find. Fixing them is often the hard part. Good luck.

- If you do fix a problem by improving a proxy measurement, you should

verify that it also improves a power measurement or estimate. That

way you know the fix had a genuine effect.

## Further reading

Chapter 13 of the [Intel optimization

has many details about optimizing for power consumption. Section 13.5

("Tuning Software for Intelligent Power Consumption") in particular is

worth reading.